In late June 2020, Wirecard shocked the world by stating that the €1.9bn missing from its accounts may have never existed. While financial scandals may not be once in a blue moon, a scandal this size is unprecedented in Germany. Due to the sheer magnitude of the scandal and how it rocked the market, Wirecard is now dubbed the “Enron of Germany” by commenters.

Wirecard is far from the only institution that is troubled by the scandal. Wirecard’s scandal has made investors question Wirecard’s auditor, EY, and BaFin, Germany’s financial watchdog. In this blog, we are going to discover how the largest fintech company in Europe has fallen from grace, and what could investors do to avoid frauds like this.

A high-flyer

Wirecard had a remarkable journey. Established in 1999, the company began as a popular online payment service by online players (in pornography and online gambling). From that on, Wirecard blossomed. The firm has grown to an established processor of payments with partnerships with a variety of online financial vendors.

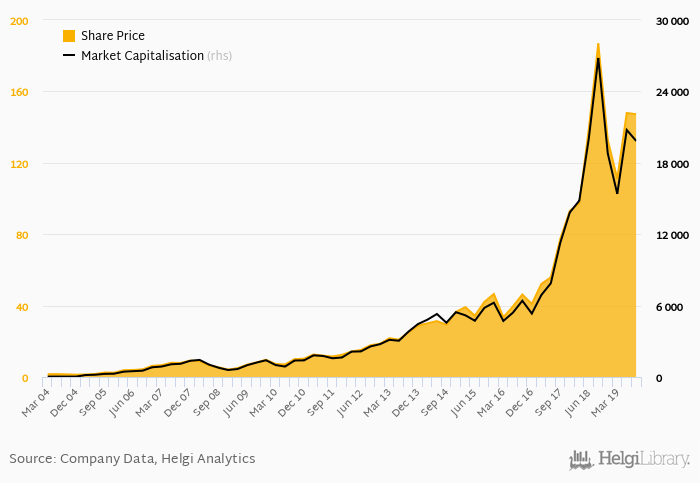

In 2018, Wirecard overtook Deutsche Bank and became Germany’s most valuable financial services company publicly listed. Moreover, Commerzbank conceded its place in the DAX 30 index to Wirecard. As Europe’s largest fintech company as well as one of the hottest European stock, Wirecard was once thought of as a company that could challenge the technology giants from Silicon Valley.

Inconsistencies and questions

Wirecard’s meteoric growth came with many unanswered questions and concerns throughout the year. The questions revolving around Wirecard’s balance sheet and accounts started years ago. In 2008, the head of a German shareholder association pointed out that there are irregularities within the company’s balance sheet. EY was due to conduct a special audit on this case, but the following year the firm that acted as the special auditor was replaced. The German authorities ended up taking legal actions against the people associated with the attack on Wirecard.

In 2015, the Financial Times raised questions about the inconsistencies in the company’s account, where they suggest that there seems to be a €250 million hole. With regard to the situation, Wirecard responded with letters backed by Schillings and received support through hiring FTI consulting to manage external relationships.

In 2016, a short seller alleged the company for money laundering. In 2018, whistleblowers reported (to Financial Times) the concerns over the Singapore scandal. In 2019, Financial Times once again published documents that show fraudulent reports on profit and customers by Wirecard. However, all of the aforementioned questions and concerns were denied by Wirecard. There are even reports that the people or organizations that are critical of Wirecard have received phishing emails and hacks form unknown sources.

The final nail in the coffin

On June 5, the German police searched Wirecard’s offices after the launch of a criminal investigation against CEO Markus Braun and the three other executives. Moreover, BaFin has submitted complaints against the payment company due to Wirecard’s misleading statements made to investors ahead of the KPMG report.

2 weeks later on June 16, the two Philippine banks, BPI and BDO, where the missing €1.9bn was supposed to be held, informed EY that the documents detailing the €1.9bn are “spurious”. At this time, Wirecard was no longer able to cover their misdeeds. As a result, instead of publishing the auditing results, the company announced that the €1.9bn are missing on June 18.

After this news was announced, Wirecard’s stock price immediately crashed nearly 62% on that day, closing at €39.99, the lowest level since December 2016. Ultimately, Wirecard filed for insolvency on June 25, marking the end of the former-market darling.

Ripple effect: Widespread scrutiny of EY and Germany’s regulators

Not only did Wirecard get in deep trouble in the scandal, but EY and BaFin have also faced widespread scrutiny. While EY Germany’s inability to uncover Wirecard’s fraud would not cause an implosion of its global network like what Enron did to Arthur Anderson, the scandal will most likely cause a heavy blow on their credibility and reputation, especially with the Luckin Coffee scandal earlier this year, which was also audited by EY.

Meanwhile, many criticized BaFin for how they have dealt with past allegations against Wirecard as they have temporarily banned short-selling of Wirecard stocks in favour of the company and filed complaints against two Financial Times journalists who have investigated the fraudulent behaviours in the company. Many have attributed the failure to the regulator’s low efficiency, an insufficient delegation of supervision and fragmented responsibilities, as well as Germany’s desire for a local fintech company to thrive. In light of the criticisms, Germany’s finance minister, Olaf Scholz, has told the local newspapers that “it is now up to legislators to review and improve new protective mechanisms.”

“I want to give BaFin more control rights over financial reports, regardless of whether or not a company has a banking section,”

Olaf Scholz, Federal Minister of Germany for Finance

The priced question: What could investors do to avoid financial scandals?

So, what could investors do to avoid companies like Wirecard? Unfortunately, it is often very difficult for investors to differentiate fraudulent firms from legitimate companies, especially due to the fact that most of the former appear to be the “high-flyers” and “superstars” due to inflated financials.

Despite this, there are often signs for investors to exit the fraudulent firms before their shares become valueless. For large scale scams, there are often whistleblowers before the impending implosions, such as the two Financial Times journalists in Wirecard’s cases. While fake “whistleblowers” with malicious intent do sometimes target innocent companies, there are ways to tell whether the whistleblowers are genuine. If the company is innocent and is targeted by vicious “whistleblowers”, usually the company will be able to dispel all the allegations with proof. However, if the whistleblowers are real, and they are trying to disclose the wrongdoings of a company, the target company will try to pressure the whistleblowers to stop by any means. As Wirecard have tried to sue the Financial Times reporters without proofing their claims as false, investors actually could guess that the allegations against Wirecard are possibly true.

The takeaway

It is never easy for investors to see through financial scandals before everything is revealed. However, we should always look for signs of genuine whistle-blowing.